Naturally such a custom does not exist along Europe's Southern fringe, which doesn't mean it couldn't be invented since the young and educated are increasingly leaving much to the chagrin of those they leave behind.

But the "packing up and leaving" variant has now become the predominant one in another country suffering brain flight, one which has does have significant historical associations with traditional Russian culture: Ukraine. The suitcase mood is alive and well among a growing number of young Ukrainians, as journalist Vitaly Haidukevych discovered when he conducted an online survey on the subject via his facebook page,

"The suitcase mood is there. [...] Young, promising people have it. [...] Since they are young, they are leaving not for the sake of immediate earnings [...], but to grow roots for the future. [...] I assume that these people asked themselves whether it was possible to change the state of things in the country – and the answer was ‘no'. [...] Some are leaving for exactly the same reason others are reluctant to join [the anti-regime] protests – they care about themselves, their families and their future. [...] “what are those rapid movements for, you've got kids, think about them” – this is what those who've stayed think. And those who are leaving [...] do not want to wait for the tax authorities to come and take away their last pair of underpants. [...]"

Is Ukraine Headed For Imminent Population Meltdown?

Now, as I say, this "want out" phenomenon can now be found in many countries on Europe's periphery (here, here, here and here), but the Ukrainian case is an extreme one. So much so that the Ukrainians themselves have a word for those who have left the country in search of work and fortune elsewhere - zarobitchany. According to a 2011 report issued by the International Organization for Migration six and a half million Ukrainians, or 14.4 percent of the population, are now emigrants who have left their country (or rather they were at that point, since the 2013 number is certainly larger). Countries like Russia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Italy, Portugal and Spain are among the most popular destination countries identified in the report.

In all cases of low fertility societies young population exodus is a problem, but in Ukraine's case it is well nigh lethal. The country has a little over 45.5 inhabitants and the population is shrinking by 330,000 per year. Besides the birth/death deficit emigration obviously contributes significantly to this sharp downward demographic trend (hat tip to Ukrainian blogger Veronica Khokhlova for most of the above).

Even without emigration the population would be falling, since the birth rate is around 1.3 (well short of the 2.1 replacement level) and far more die each year than are born, but the fact that so many also chose the exit route raises deep and preoccupying questions about the future of such countries.

The latest UN population forecasts put Ukraine's population at around 30 million by the end of this century, but this number is surely a highly optimistic one, in part because it assumes some sort of fertility rebound, but more importantly because it assumes that emigration won't melt the country down much more quickly and much sooner than that. In addition to the smaller population the shifting age structures mean that the proportions of Ukrainians over 65 and over 80 will rise continuously. According to latest estimates Ukraine's population in 2050 will look something like this.

Obviously people aren't leaving because the population is declining, but rather because the economy is not able to incapable of generating sufficient economic growth and sufficient jobs to encourage people to stay. There is a loss of confidence in the future of the country because the economic decadence becomes associated with degeneration in the political system.

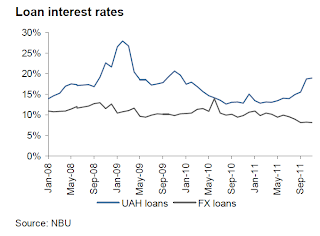

Decadence certainly seems to have set in at the economic level. The economy fell by nearly 15% in 2009, recovered growth of 4-5% a year in 2010/11 and then fell back into recession in the second half of 2012 (in which year overall growth was effectively zero. The IMF forecast a further year of zero growth in 2013 followed by a return to 3% growth thereafter. This subsequent out come may be very optimistic, and the country will possibly suffer from weak growth from hereon in, before eventually turning negative.

In this context the feeling inevitably grows that there is no way to turn the situation round. This feeling feeds on itself, and the big question is whether it produces a kind of circularity whereby the loss of confidence and the loss of people also feeds back into the economic process making the lack of growth and employment even worse.

Low Fertility Trap?

Such seems to be the situation Ukraine finds itself in, and naturally the frustration can be seen everywhere. As one comment on Vitaly Haidukevych's Facebook thread put it, "It's futile to expect economic growth in Ukraine. Everyone is trying to escape from it as quickly as possible." Another said, more ironically, "One has to leave quietly, or else they'll soon introduce a tax on leaving." Others are more passionate and apparently even more determined:

"People ran, are running and will run. So many have left [Western Ukraine] for Italy, Portugal and the Czech Republic, and have not returned, and more will leave. It's just that [mostly people from] the provinces used to be leaving before, and now Kyiv is moving as well. People are taking their kids to study to Poland and some even further! It's a difficult situation in the EU now, but it's still livable, while in Yanukovych's Ukraine it's 100 times harder! Me, I came to the Czech Republic five days ago, sit here without a job, but I'm not going back home".All of this puts me in mind of a fertility model developed by the Austrian demographer Wolfgang Lutz which he called the low fertility trap hypothesis. In developing this hypothesis his starting point was the assessment that "there is no good theory in the social sciences that would tell us whether fertility in low-fertility countries is likely to recover in the future, stay around its current level or continue to fall". He then goes on to advance "a clearly defined hypothesis which describes plausible self-reinforcing mechanisms that would result, if unchecked, in a continued decrease of the number of births in the countries affected". Claus Vistesen wrote up a description of the hypothesis on the Demography Matters blog (back in 2007) and I have some notes here.

Obviously the number of live births fluctuates according to the number of women in a given population who are of childbearing age, which can be more or less depending on the size of the cohorts involved. But in general terms a country with 1.3 or 1.4 fertility will have steadily less and less children as cohort size drops. This is basically population melt-down, and this critical state can be triggered by a number of processes, including social and economic ones. Some country's, as well as possibly being caught in fertility traps are also caught in liquidity ones, a connection which has not escaped the notice of Nobel economist Paul Krugman. While Krugman is surely not familiar with the fertility trap literature, he sees clearly that the low fertility Japan has experienced over decades has played an important part in the country getting stuck in a liquidity trap.

As he puts it: "Why is Japan in this [liquidity trap - EH) situation? A debt overhang from the 1980s bubble surely started the process; but surely it’s reasonable to suggest that the demography also contributes, since a declining working-age population depresses the demand for investment".

Lutz already suspected that their might well be an economic feedback mechanism that would work to drive the number of children born in a country ever further downwards towards lower and lower levels, but I think the experience of the crisis has made this pathway a little clearer, in that those low fertility countries whose economic trajectories fall off a stable growth path may find it ever more difficult to get back on one again. In street jargon they could fall into a "lose-lose" dynamic driven by low-living-standards low-growth expectations and high unemployment. Not only do such negative economic conditions discourage young people from forming families and having children (obvious I think), they can also have the effect that young people leave in search of a better future thus reducing the potential number of children who can be born in the future.

The ensuing acceleration in the rate of population ageing and the proportions of older people only makes the problem of sustaining public spending on pensions and health systems worse and worse, causing the fiscal burden on those who stay to grow and grow, a development which makes it more and more attractive to leave and start up again elsewhere. And with each additional person who leaves there is another turn of the screw, and the costs of staying get higher, as do the advantages of not doing so. This is how melt down can happen.

Naturally there can be a political dimension to the disintegration, as the need to implement ever less popular policies (especially policies unpopular with older people, those who do vote) leads politicians to become more and more demagogic while delivering less and less. Naturally the democratic quality of a country's institutions starts to deteriorate under these circumstances, which only makes the young feel even more helpless and under-represented.

This outcome is now becoming plain in much of Southern Europe, but it is obviously even more evident in Ukraine, where the former Prime Minister Julia Tymoshenko is currently imprisoned, a decision which has just been roundly criticised by the European Court of Human Rights.

Can Countries Actually "Die"?

So where does all this lead. Well it leads me personally to ask the question whether it is not possible that some countries will actually die, in the sense of becoming totally unsustainable, and whether or not the international community doesn't need to start thinking about a country resolution mechanism somewhat along the lines of the one which has been so recently debated in Europe for dealing with failed banks.

That something like this is going to be needed I regard as being what John Locke would have termed a "self evident truth". As we know, in country after country each generation is getting smaller. While we can argue about exact timing, what this falling population means means is that GDP will eventually start to contract. This should make those ecologists who have long been arguing that the planet was over populated and that zero of even negative economic growth was desirable extremely happy. But what about the debt left behind by earlier generations, will that also contract? The Japan experience so far tends to suggest it won't, and herein lies the rub.

But this is only part of the problem, since the process of country decline, like most processes in the macro economic world, is non linear. That is to say critical moments or turning points will exist when suddenly things move a lot faster than expected. Hemmingway grasped the essence of this in his much quoted "bankruptcy comes slowly at first but then all of a sudden". As the economy falls back, and the burden of debt grows on the ever smaller numbers of young people expected to pay, the pressure on those young people to pack their bags and leave simply mounts and mounts, accelerating the process even further.

In fact populations dying out is nothing new in human history if we move beyond the most recent world delineated by nation states. In hunter gatherer times populations occupied increased or reduced proportions of the earth's surface as climate dictated. In more modern times, islands have been populated or become depopulated according to economic dynamics (think the Scottish coastline). More recently, it is clear the old East Germany would have become a country in need of "resolution" had it not sneaked in under the umbrella of the Federal Republic. Why people should find the idea of country failure so contentious I am not sure, perhaps we have just become accustomed not to have "hard" thoughts.

Applying the argument many apply to banks, unsustainable countries "deserve" to fail, don't they? Why should the US or German taxpayer have pay to keep them afloat? Naturally, including Spain in this group of countries that can only now salute Cesar as they prepare to die my seem extreme, but just give it time.

I expect (should I say "predict" in the Popperian sense, since this argument IS empirical, and is surely falsifiable) the first countries to die to be in Eastern Europe, with the most likely candidates to get the ball rolling being Belarus, Ukraine and Serbia. But then gradually this phenomenon will spread along the EU periphery, from East to South. Latvia's own president said recently that if the net outflow of population was not stopped, within a decade the country's independence would not be sustainable. I don't think he was exaggerating.

So, as these countries "die", we (the rest of the international community) will have to decide what to do about them. A country "resolution" programme should be considered. The scale of the humanitarian tragedy will not be small.

Now, from time to time conventional economists do start to have a glimpse of what is really going on. This happened to Paul Krugman a month or so ago when he came up with the memorable phrase that part of Japan's economic problem was the result of a growing "shortage of Japanese". Now, as I am trying to suggest, this shortage is not simply a local, Japan specific, phenomenon, but forms part of a global pattern. Again, exact timing isn't clear, but sometime in the second half of this century global population will peak, and the shortage will steadily spread to take in all countries. To quote Krugman (in an earlier piece) again, at that point "to which planet will we all export"? Answers on a single piece of paper, in a plain white envelope, please.

But not all countries will experience the shortage (which is already being talked about in China in labour force terms) in the same way. Some countries, with competitive economies, healthier banking systems, younger populations, and better-quality institutions will gain the population which is being lost by the others. That is another of the reasons I say the process will not be linear. This is naked capitalism in the raw, sovereign against sovereign, with a winner take all structure.

So the modern economic system becomes something like the game musical chairs. When the music is playing everyone gets up to dance, but each time it stops there is one less chair (country) to fall back on. And so it goes on and on, through numerous iterations. Now where's my suitcase.

Postscript

I have established a dedicated Facebook page to campaign for the EU to take the issue of emigration from countries on Europe's periphery more seriously, in particular by insisting member states measure the problem more adequately and having Eurostat incorporate population migrations as an indicator in the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure Scoreboard in just the same way current account balances are. If you agree with me that this is a significant problem that needs to be given more importance then please take the time to click "like" on the page. I realize it is a tiny initiative in the face of what could become a huge problem, but sometime great things from little seeds to grow.